2004 Student Art Show

May 5 - May 27, 2004

by Tony Callendrillo

by Tony Callendrillo

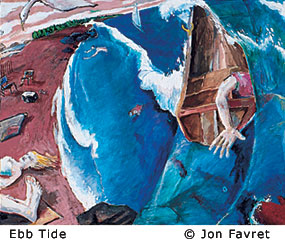

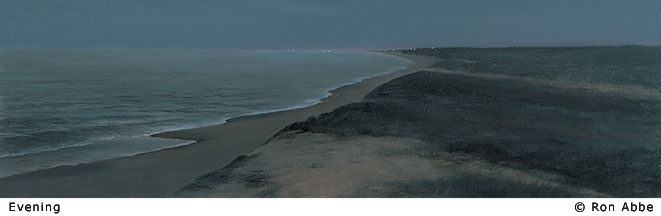

Jon Favret and Ron Abbe

|

© 2004 Jenny Holzer / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York © 1997 antenna tool & die co. All rights reserved |

|

January 22 - March 26, 2004 Opening Reception: Thursday, January 29, 2004, 12:30 - 2:30 pm Curated by Robbin Zella |

|

The Housatonic Museum of Art will present Interface: Jenny Holzer and Media Art curated by Robbin Zella from January 22 through to March 26, 2004. There will be an opening reception Thursday, January 29th from 12:30 until 2:30pm in the gallery. This event is free and the public is cordially invited to attend.

Since Jenny Holzer’s Truisms first appeared on the streets of New York in 1977, she has been steadily developing a method of appropriation and quotation to offer a feminist critique of a consumer society. Her Truisms – a series of one-line texts presented to the viewer in unexpected places- have been printed on glasses, T-shirts, golf-balls, coffee mugs, and pencils; they have been carved into benches and picnic tables, and encoded into LEDs, inserted as commercials on cable and network television in California and Connecticut (Art Breaks), and published on the Internet (ada-web). All of the vehicles that Holzer has selected for her words are also used in advertising. By appropriating an established public or commercial site and by using a form of quotation, such as mimicking advertising slogans, she is able to subvert both the vehicle and the message to offer an investigation into the values of our society. For example, in 1982 Holzer was invited to create a project through the Public Art Fund in New York City. She programmed the Times Square Spectacolor Board with selections from her Truisms, on of which was PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT. As this ironic plea hovered silently above the crowd, it created a rupture in the physical environment of advertising messages and purchasing directives and a gap through which awareness of an economic issue or a personal lifestyle choice could emerge.

Holzer’s Lustmord series developed as her response to the fighting in Bosnia and, more specific, to crimes against women committed during the war. Images can advance a point of view, manipulated by what we see and, as importantly, what we don’t see. Holzer’s juxtaposition of media-text and photography-creates a poignant image of warfare. She photographs text written on women’s skin, powerfully stating that these bodies have become sites of conflict. Through a strong narrative text, she projects an image of society in which such conflict, on or off the battlefield, exists; privilege, consent, authorization, permission, justification, power and powerlessness are the subtexts of these works.

Similarly, her Laments series (vertical LED diptych) reveals the rules and structures underlying personal behavior and social systems.

Ultimately, Jenny Holzer emerges as an artist/activist working in opposition to established authority as represented by the popular media. She penetrates our communication systems, our vehicles of communication- paper, stone, electronic signage, television, and computers, in order to dissect our beliefs and expose the contradictions within our social reality.

Jenny Holzer was born in Gallipolis, Ohio on July 29, 1950. She studied at Duke University for two years before transferring to the University of Chicago. Holzer received her B.F.A. from Ohio University in 1972. She continued studying painting and printmaking at the Rhode Island School of design, where she met her husband, fellow artist Mike Glier. She was awarded her MFA from RISD in 1977 and was then accepted into the prestigious Whitney Museum Independent study program where she developed her first “Truisms.” In 1990, Holzer was selected to represent the United States in the American Pavillion, 44th Venice Biennale. Jenny Holzer lives in Hoosick Falls, New York with her husband and daughter, Lily.

Opening Reception

January 29, 2005 • 2:00 - 4:00 pm

|

|

Selections from the exhibit, click on image to view larger...

|

||||||||||||||||||||

HCC Annual Faculty Show and Annual Student Exhibition |

||

|

Opening Reception: 12:00 - 1:00 pm, Wednesday, April 6, 2005 April 7 at 12:00 noon: Michele S. Kay will discuss the Housatonic Museum of Art's collection and conservation program plans and a tour of the collection will be included.

Opening Reception: 12:00 - 1:00 pm, Wednesday, April 27, 2005 |

The Housatonic Museum of Art will offer the following films highlighting author Zora Neale Hurston and the artists of the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance encompassed an extraordinary outburst of creativity in poetry, literature, music and the visual arts.The following films will be presented in April in the Gallery:

Zora Neale Hurston was one of the most important African American women to emerge from the Harlem Renaissance. Zora Hurston was a college graduate and pursued her degree in anthropology. Hurston collected folk stories in the South as well as writing over 200 short stories and several important novels – the most celebrated Their Eyes Were Watching God. |

|

|

Announcing the first ....

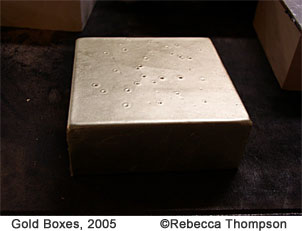

Housatonic Museum of Art Annual Open Juried ShowExhibition dates: June 10 - July 31, 2005First Prize: Rebecca ThompsonSecond Prize: Mathias AlfenHonorable Mentions:

|

Opening Reception

September 15, 2005 5:30 - 7:00 pm

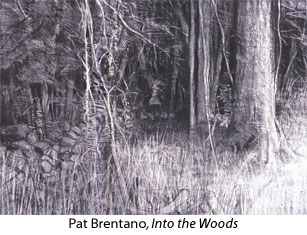

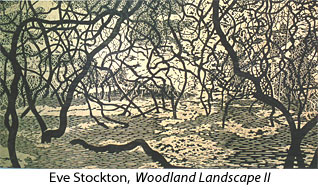

The Weir Farm Trust is pleased to return to the Housatonic Museum of Art with its 2005 Visiting Artists exhibition. It features five regional artists who have spent the past year exploring the bucolic setting of Weir Farm National Historic Site, located in the towns of Wilton and Ridgefield, CT. In its 14th year, the Visiting Artists Program is one component of the Weir Farm Trust’s Visual Artists Program. Through a rigorous application process, five regional artists are selected each year to create a cohesive body of work based on their personal experiences of Weir Farm. The site’s natural beauty and its extraordinary legacy of art history originated from J. Alden Weir, the American Impressionist painter who owned the farm from 1882 until his death in 1919. Used as a rural retreat from New York City, Weir and his colleagues such as Childe Hassam, John Twachtman, and John Singer Sargent, all who visited the farm often, were equally inspired by the exquisite landscape and tranquility that was manifest so strikingly in their paintings done at the farm.

The opening of the exhibition is September 15, 2005 from 5:30 pm – 7:00 pm and will include an artists’ discussion

at 6:00 pm. This is a opportunity to hear directly from the

artists about their artwork and how it evolved over the past year

during their visits to the site; each artist reacted differently

to the landscape and history of Weir Farm, incorporating their own

individual styles and mediums to create visual responses that when

viewed as a group reveal the remarkable depth of subject matter.

The five artists are Bob Keating, Rob Loebell, Jane

Miller, and Eve Stockton from Connecticut,

and Pat Brentano, from New Jersey.

The opening of the exhibition is September 15, 2005 from 5:30 pm – 7:00 pm and will include an artists’ discussion

at 6:00 pm. This is a opportunity to hear directly from the

artists about their artwork and how it evolved over the past year

during their visits to the site; each artist reacted differently

to the landscape and history of Weir Farm, incorporating their own

individual styles and mediums to create visual responses that when

viewed as a group reveal the remarkable depth of subject matter.

The five artists are Bob Keating, Rob Loebell, Jane

Miller, and Eve Stockton from Connecticut,

and Pat Brentano, from New Jersey.

The Weir Farm Trust was founded in 1989 as a non-profit arts organization that works in partnership with the National Park Service at the Weir Farm National Historic Site (designated in 1990), located in Wilton, Connecticut. It is one of only two sites within the National Park System that focuses on American art. Remarkably, the home, studio, farm buildings and landscape central to J. Alden Weir’s creative vision have survived intact, making it the finest remaining site associated with American Impressionism.

Through innovative visual arts programs and community activities, the Weir Farm Trust serves to broaden awareness of the Site’s extraordinary legacy. The mission is to promote public awareness of the Farm’s history and artistic tradition, facilitate its use by contemporary artists, provide educational opportunities, and preserve the Farm’s unique environment.

For more information about the Weir Farm Trust and the Visual Artists Program please call 203-761-9945.

Chris, Eve Stockton (Artist) and Tony Kirk, Director of the Center for Contemporary Printmaking.

Icons for a New Century Agent Orange: Collateral Damage in Viet NamSee what the critics

are saying about the current exhibition at the HMA. November 17 through January 13, 2006

|

||

|

Icons for a New

Century

Artists Matt Ernst and Rob Roy offer a look at the symbols that exemplify a new era in our history. Half way through the first decade of a new century and we can already count the conflicts that mark this new millennium. According to the web-site Global Security “much of the world [is] consumed in armed conflict or cultivating an uncertain peace. As of mid-2005, there were eight major Wars under way (down from 15 in 2003), with as many as 24 “lesser conflicts” ongoing with varying degrees of intensity. These conflicts are fueled by racial, ethnic or religious animosities as by ideological fervor.”

Matt Ernst and Rob Roy engage and challenge viewers by layering a multitude of meanings. These paintings are not “narratives” in the sense of telling a particular story but by using these disparate symbols they nevertheless impart meaning and force the viewer to ask questions about our society’s values, goals, methods and policies. >Matt Ernst lives and works in New York City. He received his degree from the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston. His work has been exhibited in New York, Florence, Vienna and Barcelona. Rob Roy lives in Massachusetts and teaches at Montserrat College in Beverly. He received his MFA from Yale University, School of Art and Architecture in 1971. His work is in numerous private and public collections including the Museum of Modern Art in New York. |

Agent

Orange : Collateral Damage in Viet Nam The startling black and white photographs by Magnum photographer Philip Jones Griffiths demonstrate for us the horrifying consequences of using the chemical Agent Orange during the Viet Nam war. The children in these photos were born almost 30 years since the US withdrew its troops from that country but what remained was the toxic chemical Dioxin which was used in the defoliant known as Agent Orange. The genetic mutations caused by Agent Orange continue to wage war against the civilians who continue to drink contaminated water and grow food in the contaminated soil. Agent Orange chronicles the lives of those poisoned by the defoliant used to denude the forests and jungles of Viet Nam. The defoliation military strategy was called “Operation Ranch Hand,” and according to Griffiths’ book, took as its motto “Only We Can Prevent Forests” that were applied to the sides of the aircraft used to spray the deadly chemical. Defoliation, the “Chemical Scythe,” affected huge swaths of land. Dioxin is one of the most toxic substances ever produced and one that continues to impact the lives of Vietnamese children today. Viet Nam vets suffered from the exposure to this chemical as well, contracting rare forms of cancer, lupus and other diseases but the link to Agent Orange was initially strongly denied by the American government but eventually $180 million dollars was awarded by the manufacturers of the chemicals through the US Courts. Dioxin contamination also affects the reproductive system, the endocrine matrix, the immune system, and the nervous system. But the most dramatic affect takes place in the womb as it alters the cellular activity and produces deformed fetuses. In Viet Nam the human toll continues to be ignored. Most babies die shortly after birth but others live with missing or deformed limbs, mental retardation, without eyes, with internal organs on the on the outside of their bodies, spina bifida and cerebral palsy. These photographs are Philip Jones Griffiths’ tribute to their grace and fortitude. Philip Jones Griffiths was born in Rhuddian, Wales in 1936. Griffiths was studying pharmacy and working as a part-time photographer for The Manchester Guardian, and the moved to The Observer newspaper. He covered the Algerian war in 1962 and has since covered major conflicts around the world. In 1971 his groundbreaking book Vietnam, Inc. was published and is widely recognized as changing US attitudes to the war. |

|

|

Lectures A

Retrospective Look at the Tragedy of Agent Orange, a

lecture by Arthur W. Galston Arthur W. Galston is the Eaton Professor Emeritus of Botany in the Department of Biology at Yale University and also Professor Emeritus of Forestry with the School of Forestry and environmental Studies. The author of more than 300 scientific articles in refereed journals and more than 50 articles on science and public policy, Professor Galston is a biologist specializing in chemical control of plant growth. His concerns about the social impacts of science led to his participating in a successful campaign to terminate the spraying of Agent Orange in Vietnam (1970), becoming a charter member of the Hastings Center, his membership on the Federation of American Scientists' Committee on Biological Warfare, and his involvement in the Society for Social Responsibility in Science, which he served as president in the mid 1970s. One Significant

Ghost: Stories from Viet Nam Diane Fox will be at the Housatonic Museum of Art Saturday, November 19 at 2pm to speak about her work with the disabled poor including those suffering from the effects of Agent Orange. This lecture is to augment the exhibition of select black and white photographs from the book Agent Orange: Collateral Damage in Viet Nam by Magnum photographer Philip Jones Griffiths. Diane Fox, Teaching Fellow, Asian Studies program at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York earned a master’s from Portland State University and is working toward her doctorate at the University of Washington. She was most recently coordinator of the Agent Orange educational project for the Fund for Reconciliation and Development. Fox has written for Education About Asia, Viet Nam News and contributed to Synthetic Planet: Chemical Politics and the Hazards of Modern Life. While at Portland State she taught various courses on Viet Nam history. This event is free and the public is cordially invited to attend. |

||

Connecticut Post December 10, 2005

BRIDGEPORT — Arthur W. Galston did not invent Agent Orange.

He didn't even get credit for its model, a defoliant he developed as a University of Illinois grad student in 1943 before he rushed off to war without getting a patent.

Yet four decades after the toxic compound began ravaging plants, and then people, Galston speaks about the topic like a man out to make amends.

"I feel this responsibility," Galston, who lives in Orange, said recently during a lecture at Housatonic Community College art gallery.

At the HCC art gallery, surrounded by a black-and-white photo exhibit depicting people poisoned by Agent Orange, Galston urged those in the small audience planning careers in science to know that anything they do could some day be used in a harmful way.

"Look at me — I was a botanist," said Galston. "I inadvertently found something which, further developed, was used as an instrument of war."

All these years later, Galston, 85, a scientist and professor emeritus at Yale University, teaches bio-ethics, a discipline that examines the social and ethical consequences of scientific research.

His lecture drew people new to the topic as well as people fighting to get reparations for the victims of Agent Orange, a chemical defoliant used to clear the jungle during World War II and the Vietnam War.

It was later blamed for cancer and a host of other ailments.

"I never knew," said Katrina Haravata, 19, a Housatonic student originally from the Philippines, who came to hear Galston after her curiosity was sparked by the photo exhibit.

Galston told her Agent Orange was named after the orange stripe painted around the 55-gallon drums used to store the chemical.

Also attending were Hau Nguyen and Tuan Le, journalists from a Vietnam news agency; Thu Nguyen, a Vietnamese national who suspects family members were contaminated with Agent Orange; and Constantine Kokkoris, an attorney representing Vietnamese individuals suing the Dow Chemical Co. and others over Agent Orange.

The case was dismissed in a Brooklyn, N.Y., federal court in March and is now being appealed. Galston is sympathetic but questions whether they can prove their case in court.

"I will do everything I can to help, but it's a tough job. It's not going to be easy to convince a court of law," he said.

Although Vietnamese scientists have good statistical data to show people in villages that were sprayed with Agent Orange have much higher rates of cancer and malformed babies, the scientific data to confirm that Agent Orange was the cause are scarce.

"You cannot experiment on humans," he said.

Agent Orange got its start as a defoliant during World War II when scientists discovered they could regulate the growth of plants through the infusion of various chemicals and hormones. The military was out to get rid of dense forests that often shielded the enemy.

Galston, a graduate student working on a doctorate at the University of Illinois, wasn't trying to kill plants, just hasten the growth of soybeans in Illinois' short summers.

He was successful in finding a compound that produced flowering two weeks earlier. But he discovered if he used too high a concentration, it also made the leaves fall off as he noted in his thesis before heading off to serve in World War II.

He returned to find that someone else had read his work and had the idea patented. His compound and others were the basis for Agent Orange.

By the time the Vietnam War arrived, it was ready for use. Millions of gallons were sprayed over Vietnam from 1961 to 1970, exposing the Ho Chi Minh trail and other enemy passageways and causing a tremendous amount of ecological damage.

Valuable teak trees and mangrove swamps along the estuaries of the delta south of Saigon were stripped and remain so to this day.

Once aware of the ecological damage the chemical was causing, Galston and other scientists went to Vietnam.

They began to wonder about the effects on people and animals. When they returned, a committee was formed to study the impact of the spraying.

A November 1967 study Galstonled was unable to come to firm conclusions about Agent Orange but advised its continued use might "be harmful" and have unforeseen consequences.

The spraying was stopped in 1970 after Galston and others successfully appealed to the Nixon administration.

"That was an important victory," he said, adding that the war continued until 1975, and the decision to stop using Agent Orange "probably averted a good deal of damage."

Still, damage has run into the billions. To this day, the United States has not spent $1 in aid to restore any of the affected areas, Galston said.

"I consider it a matter of conscience that our wealthy country, having produced so much damage, should take some action," he said.

In 1990, Galston helped to organize a Bioethics Project at Yale and is a member of the Society for Social Responsibility in Science. He has had more than 300 scientific articles published.

"Agent Orange: Collateral Damage in Vietnam," a photographic exhibit by Magnum photographer Philip Jones Griffith, runs through Jan. 13 in the Housatonic Museum of Art.

Linda Conner Lambeck, who covers regional education issues, can be reached at330-6218.

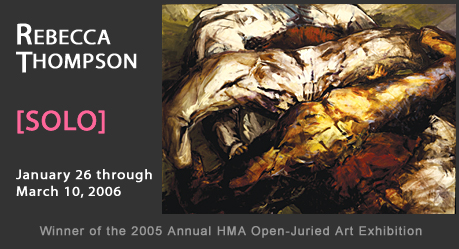

January 26 through March 10, 2006

Opening Reception January 26 • 5:00 - 7:00 pm

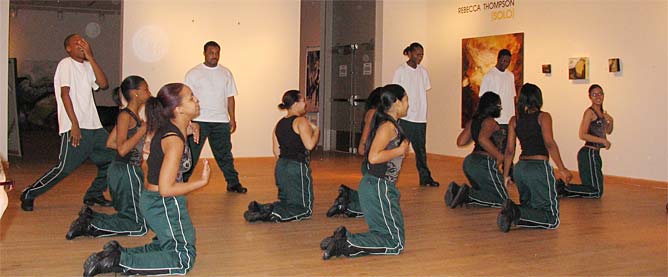

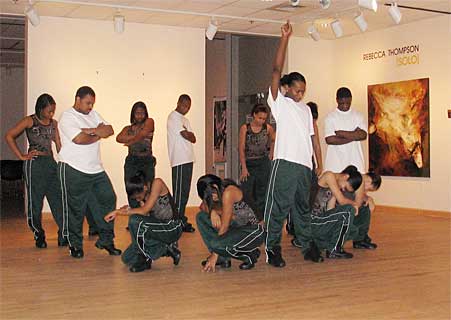

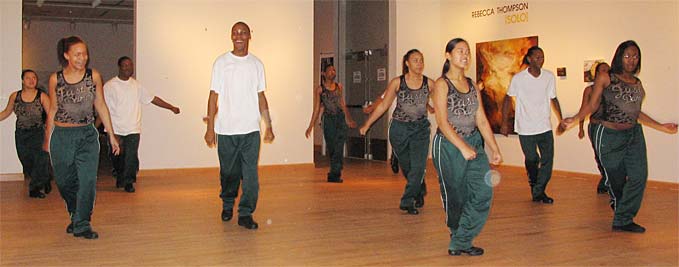

The kids from HCC's Early Childhood Laboratory School joined in with some moves of their own!

January 26 through March 10, 2006

Opening Reception January 26 • 5:00 - 7:00 pm

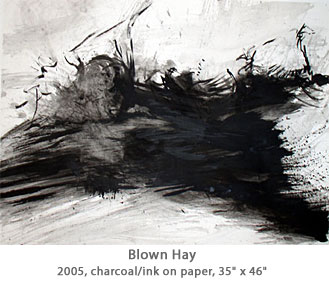

Compelling in both their strength and subtlety, the artworks of Rebecca Thompson are visually and metaphorically seductive. Their humanity invites the viewer to unravel their secrets and to unleash their potent energy. As portals into private reflection, the depth of the pieces’ dramatic yet meditative expression is heightened by the elegant richness of their aesthetics.

Thompson assimilates a broad range of experiences and inspirations,

synthesizing the spectrum of influences into a cohesive essence. Raised

on a horse farm in Kansas City, Missouri, she draws on her background

to shape her philosophy and to guide her artistic exploration. Recollections

of her upbringing often appear as powerful images that serve as leitmotifs

for her subject matter and as springboards for insight and contemplation.

Thompson assimilates a broad range of experiences and inspirations,

synthesizing the spectrum of influences into a cohesive essence. Raised

on a horse farm in Kansas City, Missouri, she draws on her background

to shape her philosophy and to guide her artistic exploration. Recollections

of her upbringing often appear as powerful images that serve as leitmotifs

for her subject matter and as springboards for insight and contemplation.

Puncture represents the genesis of Thompson’s body of work that is rich with personal symbols. Bull horns appear to jut through the surface of the painting with dynamic force. References to bulls, an iconic presence in rural areas, conjure up archetypal symbolic meanings. Personifying strength, fortitude, and fertility, the bull dominates the farm just as it permeates mythology and ancient traditions. Gestural brushstrokes infuse Bullock with drama; a bull’s horn cuts a swath across the picture plane and culminates in a vortex formed by a man unveiling himself from a mask. Thompson pushes figuration to its limits to expressive effect.

In Two Head Perspective the artist explores the formal qualities of the composition, using the bull and man imagery as a source for her ongoing narrative. The restrained tonalities of color and the interplay between negative and positive space make the image subservient to the impact of the powerfully structured yet seemingly spontaneous brushstrokes. The bold calligraphic lines revisited in her ink and charcoal drawings reflect Eastern traditions familiar to the artist through her numerous trips to China; her practice of making marks and allowing them to intuitively develop are here freed to complete abstraction. Liberated from color and form, their urgency explodes beyond the confines of the picture plane.

The physicality of the torso figures in Thompson’s series of pastel drawings contains the same innate tension on the verge of being released. The richness of the surfaces and the fluidity of the lines suggest a story unfolding, a memory resurfacing.

The delicacy of the Cutis paintings belies their vital spirit. Their

skinlike surface as implied by the title is achieved through the application

of layers of paint on aluminum, producing an interplay of transparency

and depth. Their rhythmic blending of light and color dissolve

into an intimation of renewal and regeneration.

The delicacy of the Cutis paintings belies their vital spirit. Their

skinlike surface as implied by the title is achieved through the application

of layers of paint on aluminum, producing an interplay of transparency

and depth. Their rhythmic blending of light and color dissolve

into an intimation of renewal and regeneration.

Gilded boxes create a jewellike collage and provide a serene counterpoint to the intensity of the other works. Varied surfaces—pristine, pinholed, punctured, crackled—emerge naturally during the process of layering the gold leaf, evoking an illusion of three-dimensionality that is reiterated by the depth of the wooden supports. The preciousness of the gold recalls the gilded pages and Renaissance paintings of the family Bible of her childhood.

The combined complexity of Rebecca Thompson’s subject matter and her mastery of her media earned her this exhibition as first prize in the 2005 Housatonic Museum of Art Annual Open Juried Art Show. Juror Judy Kim, Curator of Exhibitions of the American Federation of Arts, was drawn to Thompson’s work as it “possesses a monumentality that comes from her keen sense of composition and efficiency in line.” Her pieces linger in one’s mind, sparking our imagination while expanding the boundaries of emotional participation.

Marianne Brunson Frisch

The Burt Chernow Galleries will be closed for installation until Wednesday, March 11, 2026.

Please join us that evening from 5:30pm – 7pm for the opening reception of "Less Me, More We: CT State Housatonic Faculty & Staff Exhibition."

Choose your desired language: