|

The companion book, Illustrating Connecticut: People, Place, Things, will be available for purchase during the exhibit for $20, or you may purchase the book by mail. To purchase by mail:Please send a check for $24 (includes $4 postage and handling) made out to the Housatonic Community College Foundation and mail it to: Housatonic Community College Foundation |

|

Explore

by Region

|

|

AMERICAN ILLUSTRATION: A BRIEF HISTORY

Susan E. Meyer

For nearly seven centuries all artists in the Western hemisphere were employed to display the wealth and power of their patrons. In the nineteenth century, however, a change occurred and the publishing industry – replacing all traditional patrons – emerged as the chief employer of artists. The publications succeeded both church and court as the great showcase for artists, and illustration, a creation of the Industrial Revolution, became the significant avenue for the artist.

At the end of the nineteenth century and during the early decades of the twentieth, books and periodicals provided the major source of public entertainment. Consequently, the contributors appearing in those pages — the writers and illustrators – assumed an importance of unprecedented proportions. Now that publishing has surrendered its exclusive power, overshadowed by the more pervasive presence of television and the Internet, it is not easy for the contemporary reader to imagine the extent of the artist's influence on the public mind. Illustrators had a crucial role in governing the cultural appetites of the day, and no American of that period could possibly remain unaffected by the millions of pictures circulated each week.

The years between 1865 and 1917 represent publishing's most exciting and dramatic time of expansion. This era, known as the Golden Age of Illustration, shaped the American character as we know it today and illustrators became inextricably linked to the development of an industry whose main purpose is to embrace the aspirations of an entire nation, to create the American Dream.

During this time period, Hartford became a major publishing center, attracting great writers of the day, such as Mark Twain and the African-American poet Jupiter Hammond. The expansion of the publishing industry was in direct correlation to the growth of American industry, with Connecticut a central hub. After all, the ingredients needed for the success of publishing were the same as those required for the expansion of any industry: a sufficiently large market, an economical method of manufacture, and an efficient means of distribution. All three of these components fell neatly into place in America after the Civil War.

The explosion of books and periodicals produced was a direct result of America's growing demand for reading matter that had increased substantially after the Civil War. The widespread introduction of public education throughout the nation had greatly reduced illiteracy, and more Americans than ever now possessed reading skills. Public libraries – another great American institution that expanded substantially after the Civil War as a result of legislation and private philanthropy – provided ready access to reading matter. If an appetite for reading had been created by public schools and libraries, private industry had also given Americans the increased time and income needed for reading. Reader consumerism was a direct outgrowth of the Industrial Revolution.

The success of publishing periodicals depends not only on readers, however, but on advertisers as well. The expansion of industry after the Civil War meant new wares to be sold, and periodicals provided the vehicles for manufacturers to hawk their merchandise, competing against their rivals in these pages for a greater share of the market. Starting with the first magazine to carry pages of advertising (Scribner's in 1887), this source of income grew increasingly important with the years.

While the market had developed, so had the means of distribution. The growing network of railroads provided an economical and rapid method of carriage across the nation. The improved transportation system also allowed artists to live further away from their employers and Westport and Weston soon became home to prominent artists and illustrators, including Karl Anderson, George Hand Wright, Rose O'Neill, John Held, Jr., and Arthur Dove. Later the Famous Artists School, founded by Albert Dorne along with Norman Rockwell, offered courses with leading illustrators such as Stevan Dohanos, Al Parker, Austin Briggs, Ben Stahl, John Whitcomb, Peter Helck, Harold von Schmidt, Robert Fawcett, John Atherton, and Fred Ludekens. Equally significant, a new postal law in 1885 reduced the rate for second-class matter to cent a pound and a rural free delivery system was instituted in 1897. Newsstand distribution became its own kind of business, beginning with the founding of the American News Company. With this merger, the principal retail and the primary wholesale periodical businesses in the nation were united.

Because of the greater dependence on advertising for income, the emphasis was increasingly placed on acquiring more readers at any cost. Sophisticated methods of expanding circulation were instituted – such as premiums – and it became less important to distribute magazines economically, but mandatory to reach more and more readers to attract larger advertising revenues. A circulation of 100,000 may have been considerable in 1890, but relatively insignificant by 1910. Every literate American was reading published material.

Technological improvement had as great an impact on the publishing industry as it had on other industries. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the rotary press was introduced, a machine that enabled publishers to produce larger editions more rapidly and at lower cost. Of all the technological advances, however, none was more important to the American illustrator than the improvements made in pictorial reproduction. The significance of this advancement is worthy of greater elaboration here, since it is the single most important factor in making it possible for artists to expand their creative powers, liberated from the limitations formerly imposed upon them. This freedom hastened the development of illustration as a popular art.

Until the 1880s all reproduction was accomplished by means of wood engraving. The task of preparing the art was arduous and restrictive. On boxwood imported from Syria, the art would be prepared for printing. Boxwood is finely grained, ideal for engraving, but small in size because of the relatively small torso of boxwood trees. A large illustration might require a composite of several blocks… it would take an expert engraver ten or twelve hours to complete a wood engraving 5 x 4 inches in size. A full-page illustration would normally require one week to engrave.

In the 1870s one small technical advance improved the results for those artists preferring to create tonal works; the black-line was substituted by a white-line engraving. In the black-line engraving forms had been defined by areas of wood in high relief that carried the ink. With the white-line method the reverse is true, and the engraver was able to use flecks, dots, or lines to describe tones on the surface of the block. Frederic Remington took advantage of this minor technical advancement, preferring to work realistically whenever possible. Traditional pen and ink artists, such as Howard Pyle and A.B. Frost, however, continued to work with black-line engraving.

Artists found it difficult to accept the fact that their drawings were one step in a complex sequence of operations. (In many instances the engraver actually shared the credit for the illustration by signing his name alongside that of the artist.) The artist was beholden to the engraver, knowing full well that his reproduced illustration was only as good as the craftsman translating the work onto the block. An artist whose style was individual was particularly susceptible to mistranslation. In the hands of a mediocre craftsman his work could be destroyed. It is no wonder that bitterness and animosity often arose between artists and engravers.

Engraving improved greatly throughout the nineteenth century, primarily because of the great number of European craftsman to enter this country, but the cost of reproduction was extremely high. An average engraver received from $25.00 to $50.00 a week (some even higher), and the House of Harper claimed that it ultimately cost about $500.00 to engrave an average full-page block.

When photography was introduced into the printing process all this was to ultimately change. The photo-mechanical operation of translating the image to the plate by means of creating a photographic negative permitted the reduction or enlargement of the original design for reproduction. By using the electrotype process (known since 1839), a metal relief plate could be created mechanically from the photographic image, eliminating the need for wood engravers to perform comparable operations by hand. While the engraving of line drawings could be accomplished with relative ease, tonal work required a system of breaking up the continual tones into separate printing elements in order to simulate the middle (or half) tones between black and white. The so-called "halftone" process of photo-engraving provided the solution. With this method, the art was photographed with a large camera through a sheet of glass on which a series of cross lines had been finely and expertly drawn. This photograph would result in a screen negative, the lines of the glass breaking up the tones of the original art into a series of dots, larger or smaller, densely or sparsely populated, depending on the nature of the tones in the original subject. These dots could then be etched into the plate chemically so that the image would be translated onto the final printing surface mechanically in the form suitable for reproduction.

During the 1880s the publications experimented extensively with the halftone method of engraving. After the first commercial application of the screen process appeared in the New York Daily Graphic (a picture entitled "Shantytown"), the other halftones were seen more and more frequently. These early examples tended to be flat and muddy, and engravers were still employed to improve upon the plates produced the process. But by 1900 halftone reproduction – and the results obtained on the clay-coated papers created specially for the new process – had advanced so greatly that staff artists and engraving departments could be dispensed with altogether. No longer could the engraver be blamed for a poor illustration. No longer could poor draftsmanship be concealed with slapdash techniques. The new process recorded everything; it could display the best qualities of an expert illustrator, and expose the deficiencies of the less qualified. In turn, the newly developed screen halftone process created a preference for realistic pictures, fully modeled, and a new school of illustrators emerged to meet this popular demand.

Because of these technological, social, and economic developments, hundreds of publishing companies naturally emerged to produce a vast array of books and periodicals. It became a vigorous and aggressive industry that far out rivaled European counterparts. From this large field, only a few companies actually constituted the arena in which appeared America’s favorite illustrators. Yet, these few publications – and the few illustrators whose work appeared in them – represented a force in American cultural life that is almost unimaginable today. These publications had a major impact on the taste, humor, morals, and buying habits of the public, and defined the aspirations of an entire American civilization.

Today, illustration may be entering a second "golden age" although editorial illustration is no longer dominant, new avenues have opened up while older traditions, such children's illustrations, have been reinvigorated. Illustrators are well-versed in both the technology of computer software programs and traditional illustration drawing methods. As a result, traditional and digital techniques are often used in conjunction with each other. In the twenty-first century, illustration has reemerged as a key component in the creative and entertainment companies, becoming a new and significant factor in industries, such as graphic novels, video games, movies, animation, as well as advertising and publishing.

For the last eleven years, D. Dominick Lombardi has been working obsessively on the series “Post Apocalyptic Tattoos.” It began in 1998 as many artists’ projects do--with doodles in a sketchbook.

Quickly, those doodles came to resemble characters-- and as Dominick fleshed them out, they soon demanded their own world. Over the next ten years, his project mushroomed to encompass drawings in charcoal and India ink; reverse Plexiglas paintings; silkscreen and woodcut prints; and sculptures and bas reliefs assembled from pigment and papier-mache applied over junkyard detritus. He has also generated countless working drawings made with ballpoint and felt-tip pen on scraps of paper, or graphite on newsprint. Lately, Dominick has been focusing more intensively on the creatures’ environment, exploring it in the series-within-a-series he calls Graffoos--graffitti paintings made on new and old canvases.

Creatively, the project was born one night as Dominick was worrying about the fate of the universe. Its mutant creatures embody his fears and hopes for a future world, distorted by pollution, transgenic mutation, and apocalyptic events. These new people include Blue Boy, whose innards spill down his legs; his sweetheart, the rubbery-boned, turquoise-lipped Twister; Big Foot, who perambulates on a single massive foot; and Clown, who dies early on in the story from an enlarged hair follicle on his tongue. Central to the tale is the unseen Tattoo Artist, a character who chronicles his world by producing all these drawings, paintings, and sculptures.

“Are you the Tattoo Artist?” I asked Dominick once. “No,” he said. “I’m the vehicle for the Tattoo Artist who’s sending these images to me.”

Yet despite all this impending gloom and doom, Dominick’s characters pursue their distorted lives with so much spirit and joie de vivre that their universe never seems bleak. And Dominick himself has pursued the project with a zeal, intensity, and joy in craftsmanship that suggests life is truly worth living.

- Carol Kino

Return to Post Apocalyptic Tattoo: D. Dominick Lombardi’s Dark Vision Information Page

Biographies of the Curators of Polaridad Complementaria:

Recent Works from Cuba

Margarita Sánchez Prieto

(b. Havana City, 1953)

Margarita Sánchez Prieto. the co-curator of Polaridad Complementaria, is a researcher and art critic for the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam in Havana. Previously she served as curator for the Havana Biennial and for cultural institutions and universities in the Netherlands, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Venezuela, Paraguay and Canada, as well as the University of Havana. She has authored for catalogues and art magazines and has lectured on contemporary Latin American art in Cuba and abroad. She is the author of the anthology Visión del arte latinoamericano en la década de 1980 (Vision of Latin America Art in the ’80s) and of its foreword which was published by UNESCO in Lima, Perú. In 2001, she was awarded a Rockefeller scholarship for the research project Identidades en Tránsito: ante la globalización (Identities in Transit: In Face of the Globalization). Born in Havana, Prieto has juried exhibitions sponsored by the National Council of Visual Arts of the Ministry of Culture in Cuba and received the National Prize for Curatorship from the 2000 Havana Biennial. She has a Bachelor in Art History from the University of Havana, 1976.

Jorge Fernández Torres

(b. La Habana, 1965)

Jorges Fernández Torres, the curator of Polaridad Complementaria, is the Director of the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam and the Havana Biennial, where he also works as an art critic. He is a past member of the Commission for Cuban Cultural Development of UNESCO and served on the Advisory Council for the Arts of the National Library of Cuba from 2000-2001. From 1998-2008 he was Vice Rector of the Higher Institute of Arts in Havana. Torres has curated and authored catalogues for numerous exhibitions in Cuba and abroad. Among his curatorial projects are El lugar construido (The Constructed Place), Scholtter Foundation in Altea, Alicante, Spain, 2005; Three Cuban Artists, Alicante, Spain, in 2006 and 2007; Cuban selection of Imágenes multimedias de un mundo complejo. Visiones a ambos lados del Atlántico (International Video Art) organized by Granada University, Contemporary Art Centre of Sevilla, Recoleta Cultural Centre in Buenos Aires, Mytho Gallery, Mexico D.F. and Ludwig Foundation and French Alliance in Havana. A Cuban native has a Bachelor in Art History from the University of Havana, 1990, and currently serves as professor of contemporary art at the Higher Institute of Arts and lectures internationally.

Pattern, Power, Chaos and Quiet

Curated by D. Dominick Lombardi

Organized by Katharine T. Carter & Associates

February 22-March 29, 2018 (We apologize that the original closing date of March 31 was pushed ahead. This is because HCC will be closed on March 30th and March 31st in observance of Easter weekend.)

Nature-Inspired Exhibit Opens at Housatonic Museum of Art On February 22, 5:30 pm until 7:00 pm in the Burt Chernow Galleries

Eight artists will be featured in the show: Gloria Garfinkel, Brenda Giegrich, Sandra Gottlieb, Nolan Preece, John Lyon Paul, Mark Sharp, Susan Sommer and Martin Weinstein. The works take nature as its subject, and through a prism of personal, political or technological concerns, each artist strives to portray the very essence of nature.

Click here to download a PDF of the catalog.

Close to the Line

Opening September 5, 2019 At Housatonic Museum of Art

The Housatonic Museum is pleased to present Close to the Line: Mari Rantanen and Kirsten Reynolds, an investigation of geometric abstraction through a performative lens. Curated by Barbara O’Brien, the exhibition will be on view in the Burt Chernow Galleries at the Housatonic Museum Art September 5 – October 12, 2019. A reception with the artists and curator will be held on Thursday, September 5 from 6-7:30 p.m. This event is free, and the public is cordially invited to attend.

According to curator O’Brien, “Close to the Line will reconsider the history of 20th century geometric abstraction, its evolution and place in the 21st century. The expression and intention of the artist will be in active dialogue with the experience of the viewer. Large-scale works will tread lightly between painting, sculpture, architecture and the performative.”

For the exhibit “Close to the Line” Reynolds will exhibit two new architectural installations. In the main gallery, viewers can walk through “Switchback,” 2019, a tall cluster of trestle-style architectural frames connected to large fragments of decorative arcs. The arcs seem to spin or fall around a brightly painted platform, creating a theatrical “stage” of frozen movement that playfully frames the viewers’ physical engagement with the space. In the second gallery, “post” 2019 is an arrangement of faux architectural forms that interchangeably suggests an ordinary structural support, remnant of an unknown intention or an ambiguous point in a narrative of construction and demolition.

Poised between perpetual creation and imminent collapse, Reynold’s large-scale, site-specific architectural installations activate the agency of uncertainty. Her work explores the inter-relationships between language, architecture and the body as theoretical constructions that become fluid and emergent through humor, curiosity and wonder. Colorful printed patterns and faux wood grain used throughout the installations present a surface façade that complicates materiality, rendering her architectural constructions as unstable and performative. Reynold’s absurd tableaus create a space between fact and fiction that the viewer can enter, becoming a participant in an irresolvable narrative.

Reynolds has exhibited widely, most recently at the Boston Sculptors Gallery, the McIninch Gallery at Southern New Hampshire University; the Museum of Art, University of New Hampshire; the Blue Star Contemporary Museum, San Antonio, Texas; the Currier Museum, Manchester New Hampshire, and the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, Lincoln Massachusetts. She holds a BFA from Syracuse University and an MFA from Maine College of Art. Reynolds is the recipient of numerous awards including the Vermont Studio Center Fellowship, New Hampshire State Council for the Arts Artist Grant. She lives and works in Newmarket, New Hampshire with her husband and two children.

Born in Espoo, Finland, Mari Rantanen has had a distinguished, international career including a professorship at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts from 1996-2005. Commissions to design large-scale architectural public art works include the Niittykumpu Subway Station in Espoo, Finland and the Citybanan Odenplan Metro Station in Stockholm Sweden, both 2017. For more than 20 years, Rantanen has maintained a studio practice in Stockholm, Sweden, Tammela, Finland, and New York City. She studied at the School of the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki, Finland. As a Fulbright Scholar, she studied at Pratt Institute in New York City. In the past few years alone, Rantanen has had solo exhibitions in France, Finland, Sweden, Germany and the United States.

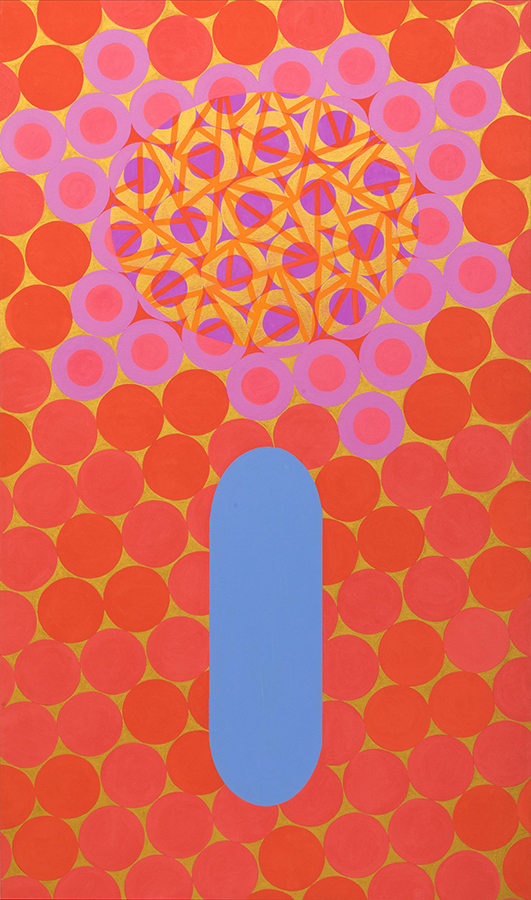

For "Close to the Line," Rantanen will premiere a large-scale triptych which will create an enveloping experience of vivid color and glowing light. A few paintings from the 2017 series "There is a Crack in Everything. That is How the Light Comes In" - will also be shown. The series title is borrowed from the song "Anthem" by Leonard Cohen. The sets of paintings, mural-like in scale, will fill the peripheral vision of the viewer and create an evolving experience as the visitor moves through the gallery, suggesting looking at an idea or subject matter from different points of departure.

Rantanen’s signature palette of glowing, bright oranges, reds, pinks and greens create a near op-art experience of vibrating geometric forms. The palette is given a classical counterpoint with the addition of gold and silver created from German pigments mixed with acrylic. A marvelous, light filled space is created through the placement of side-by-side geometric forms; ovoid, triangles, stripes, dots, and hatch marks. In her paintings, color bears the emotional quality and feelings, while the geometric forms bring a narrative quality.

“My work,” says Rantanen, “reflects life via culture. I am especially interested in architecture and painting - places people have made. The history and presence of visual culture, the different systems and patterns that make life visible both as it is seen in the everyday life as well as in the high culture are of great importance to me. I want to combine element of different cultures through my own experiences as well as interpret the experiences of others as I them understand. With my work I hope to make good places and spaces for emotions.

Barbara O’Brien is an independent curator and critic based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She was Executive Director of the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri from 2012-2017, after serving as chief curator and director of exhibitions since 2009. O’Brien is an elected member of AICA-USA, International Association of Art Critics. “I am delighted to be working with the Housatonic Museum and director Robbin Zella. I am grateful for the opportunity to bring together the art of Mari Rantanen and Kirsten Reynolds to create a dialogue around the art and artists of our time.”

Prior to her time at the Kemper Museum, O’Brien was an assistant professor in the Art & Music department at Simmons College in Boston (2006-08), editor-in-chief of Art New England magazine (2003-06) and Director of the Gallery and Visiting Artist Program at Montserrat College of Art in Beverly, MA (1990-2001). O’Brien earned an MFA from Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and in 2006 was awarded the RISD national alumni award for professional achievement.

About the Reception

A reception with the artists and curator will be held on Thursday, September 5 from 5:30PM - 7:30PM. Musician Joe Mennonna will be performing.

Joe Mennonna is a freelance musician with a wide-ranging musical career spanning liturgical and educational, as well as studio and live performing in jazz, rock, folk and classical genres. He is currently a multi-instrumentalist for actor Kevin Bacon’s band The Bacon Brothers, and is an associate organist for The Church of St. Mary in Greenwich, CT. He has toured with folk legends Tom Rush, Don McLean, Al Stewart and Janis Ian. He has scored numerous features, documentaries as well as multi-media corporate presentations for IBM, Ford, Colgate-Palmolive and other large and small companies, and appears as a keyboard or saxophone soloist on recordings with Vanessa Williams, Melba Moore, Gillan and Glover of Deep Purple, Tom Rush and Richie Havens. He is a Grammy nominee (2009, Best Musical Album for Children), and continues in record production, artist development and music instruction.

Mari Rantanen, "There is a crack in everything, that is how the light comes in #11", 2017, 72" x 44"

Kirsten Reynolds, architectural model for "post", wood and paint, 2019

Click Here To View the Images from the Gallery Opening

Click Here To Download Close to the Line Publication!

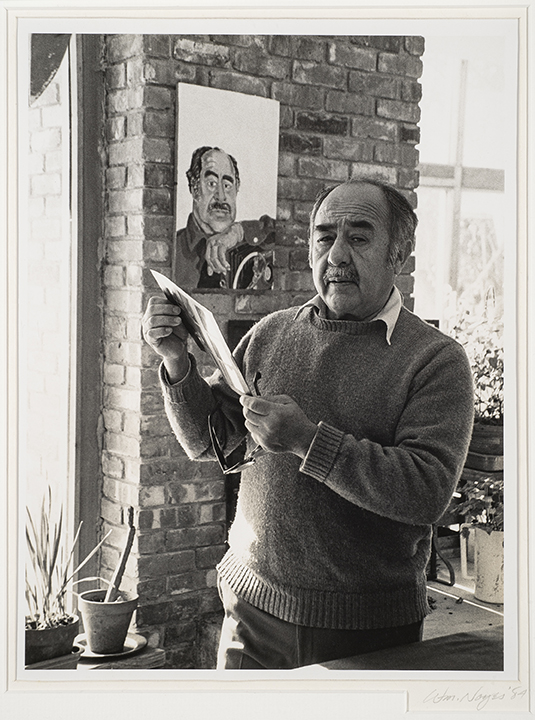

A portrait!

What could be more simple and more complex, more obvious and more profound. Charles Baudelaire

Telling Portraits

Portraits were once the exclusive province of monarchs and nobles, symbols of privilege and prosperity. With the development of the daguerreotype in 1839, working class people soon had a means of capturing their own likeness inexpensively and, by 1901, cameras like Kodak’s Brownie became so affordable, anyone could take pictures!

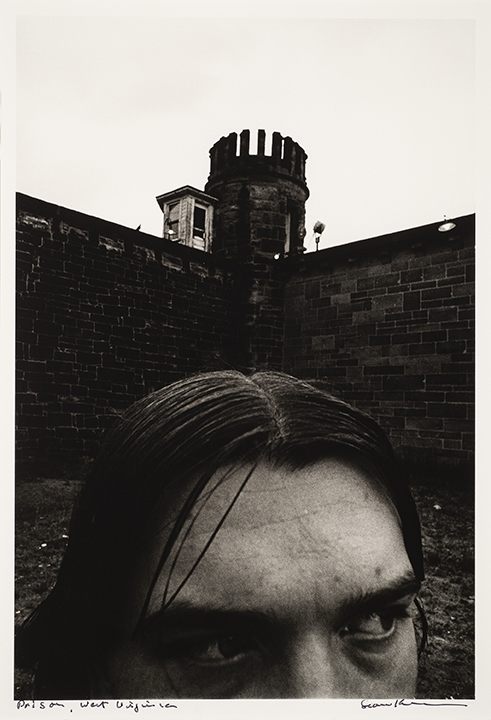

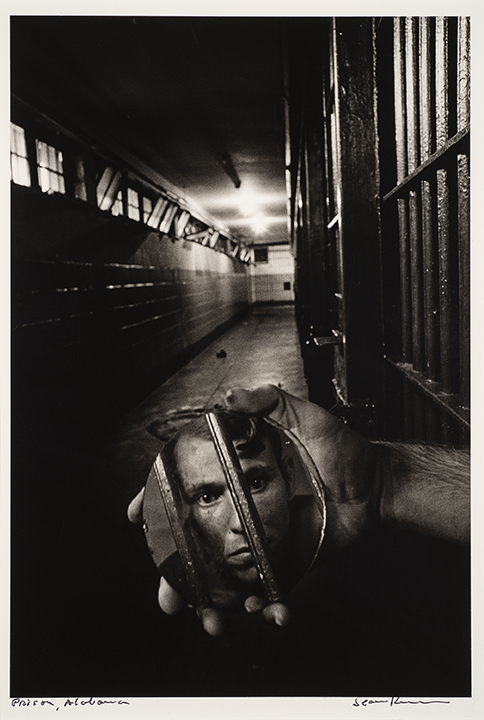

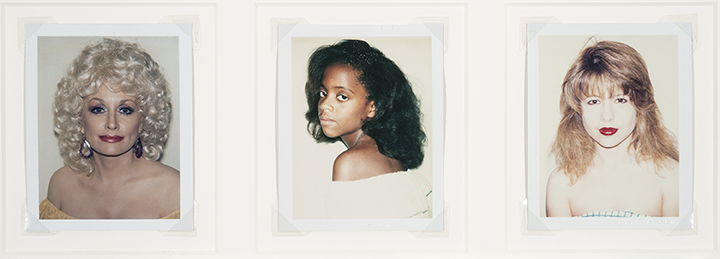

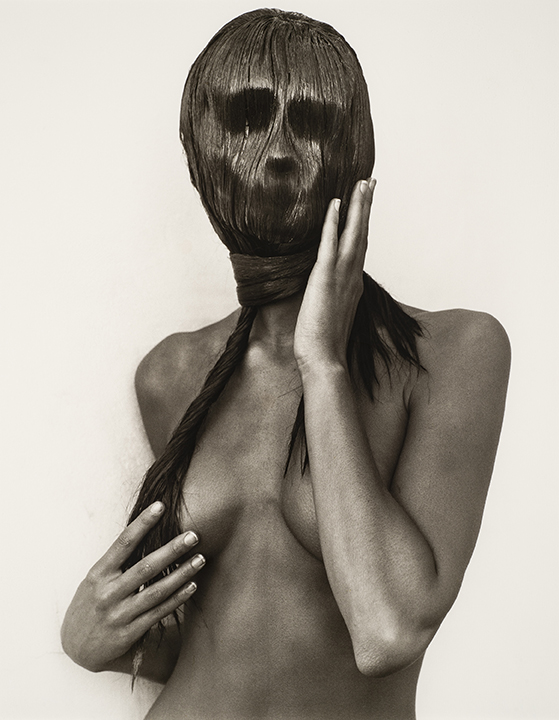

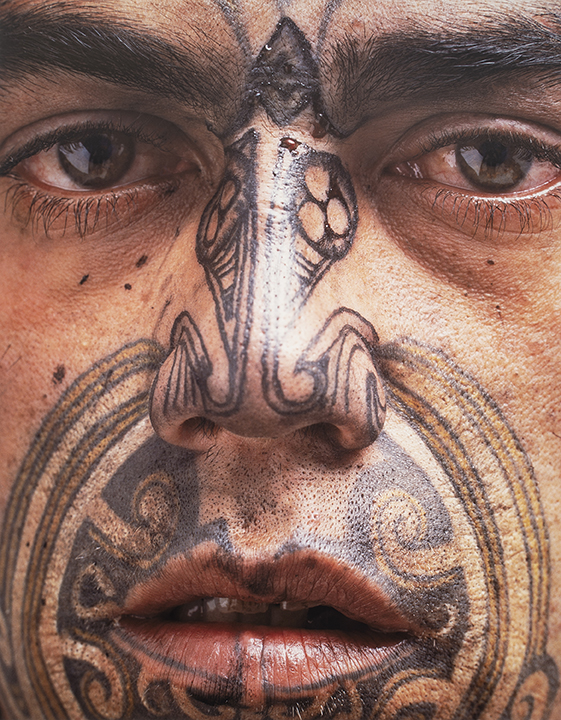

Andy Warhol, one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, comes closest to the notion of the valet de chambre or court painter. He, himself, was famous as a chronicler of the rich and famous, though his monumental paintings began as the humble Polaroids on view here. Similarly, photographer Hans Neleman records not only the likeness of his subject, but also the rich tradition of tattooing known as ta moko, a practice that signals one’s status within Maori society. In contrast, Sean Kernan’s subjects are kept separate and apart from society. Locked behind the walls of maximum security prisons, we are offered only fractured features reflected in a mirror, the very inverse of celebrity and rank.

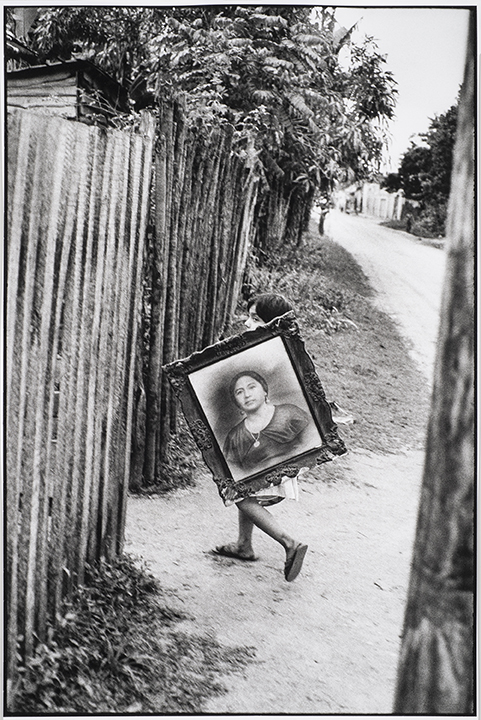

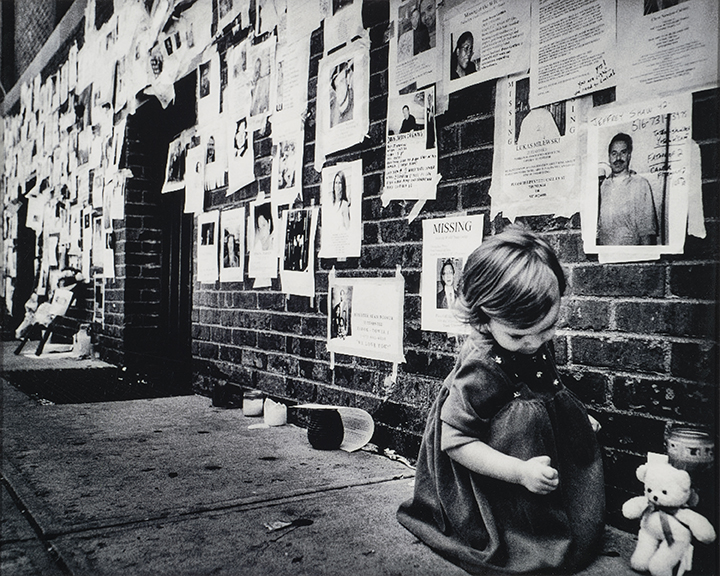

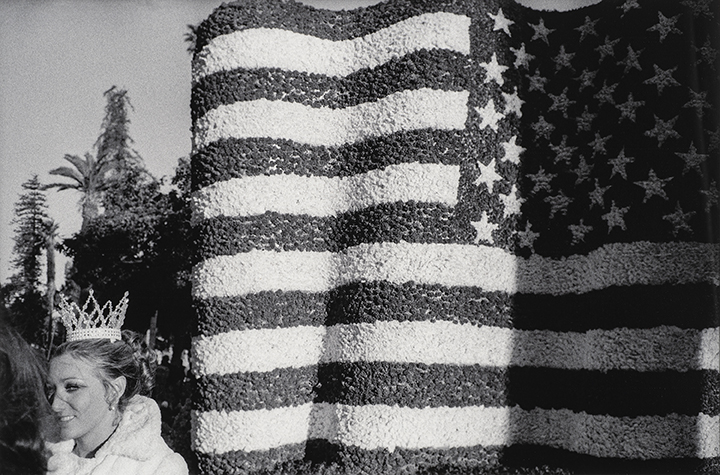

Taking pictures of people as they move about their day, unaware they are being observed, is at the very heart of candid photography. Renowned street photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, conveys a bit of humor with his “portrait” of a small child laboring to carry a portrait as large as herself. Larry Silver takes unplanned photos of people and situations as well. As a little boy gazes off into the distance unaware of Silver’s presence, his puppy stares directly into the camera lens. With over one hundred Rolling Stone covers to his credit, the celebrated portrait photographer, Mark Seliger, caught this young girl contributing her teddy bear to one of the many memorials that materialized in New York City after 9/11. These photographs are not meant to document a particular person, but rather, to capture “decisive moments” as they unfold.

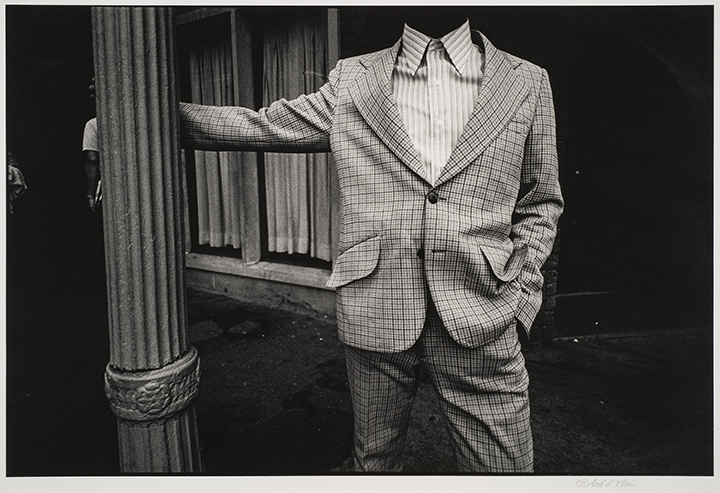

Material, motion and mood are employed by Robert Klein, Kenda North and Deborah Dancy to reveal, instead of a likeness, the personality of their subjects. A woman, fully clothed replete with red shoes, is seated at the bottom of a pool; another woman dances with her mother’s wedding dress while an “empty suit” leans against a lamp post. Sensitive and poetic or social and political, image by image, these photographs create portraits that both show and tell.

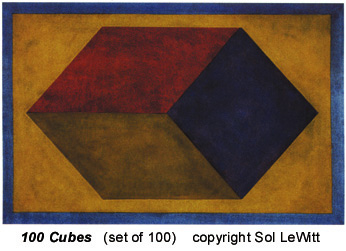

LeWitt Exhibition Opens in Burt Chernow Galleries

The elegant work of minimalist-conceptualist artist Sol LeWitt will be exhibited in the Burt Chernow Galleries of the Housatonic Museum from Thursday, January 21 through Friday, February 19, 1998

LeWitt is considered an innovator in the field of contemporary art. His work, included in major museums and collections throughout the world, and his writings continue to have significant influence on the work of conceptual artists.

Robbin Zella, director of the Housatonic Museum, says, "Conceptual art declares that the idea rather than the art is significant. The concept in the artist's mind is, essentially, more important than the object itself."

The exhibit at the Burt Chernow Galleries will feature drawings, prints and structures. The prints and drawings included in the exhibit are geometric forms which the artist explores again through structures. Zella says, "(the structures) use mathematics and logical progressions as a way of formulating arrangements."<

LeWitt was born in Hartford in 1928. He was an architectural draftsman and later taught at the Museum of Modern Art School, Cooper Union, and at New York University.

The Housatonic Museum is at Housatonic Community College, 900 Lafayette Blvd., Bridgeport, CT. The Burt Chernow Galleries are open Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., on Thursday until 7 p.m., and on Saturday from 8:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. For further information, call Robbin Zella 203-332-5052.

Personal Affects:

The Wishbone Project / The Pillow Project

June Ahrens

November 6 and continues through December 23, 1999

| Provocative. That's the word that I hope comes to mind when people explain my work. I strive to create work that questions borders, unlocks stereotypes and stimulates thought.

Whether I use pieces of soap, dirty pillows, discarded furniture, latex or gauze, the tension between self and other is always present. The work is based on an awareness that tactile material, especially those with a previous life, can provide a visceral response. It is about isolating these materials to refocus the viewers' attention toward exploring and examining their own thoughts and feelings. I feel I must step out of the comfort zone, out of the walls of my studio where I have some measure of control, to create individual pieces, installations or collaborations that involve other people. The involvement may be indirect because someone has given me materials, or direct, because others participate in my workshops to make objects that help form the whole. My hope is that the viewer can experience a connection, a recognition, a reawakening. I've been told that the response is unexpected, that it sneaks up on the viewer willing to look beyond the surface. What is my attraction to everyday materials that people have used and would otherwise throw away? Why do I solicit the work of others? They come to me as gifts, as intimate extensions of their daily experiences. I then integrate these fragments, and somehow the imprint of each person, the exchange of feeling, thought and idea, becomes an unseen force in my work. Multi-generation Collaborative HCC's Early Childhood Laboratory School participated in a project in collaboration with senior citizens to create "wishbones" of their own.

|

Artistically, I transform discarded objects to create a visual language that evokes the experiences of impermanence and loss, fragility and vulnerability, pain and most of all, healing and survival. This work has evolved from my experiences with the homeless and other marginalized communities.

Artistically, I transform discarded objects to create a visual language that evokes the experiences of impermanence and loss, fragility and vulnerability, pain and most of all, healing and survival. This work has evolved from my experiences with the homeless and other marginalized communities.