Native American Art - Virtual Tour

Native American Art - Virtual Tour

-

Cribbage Boards

Due to its rugged landscape and harsh climate, Alaska was considered the last frontier, attracting Euro-American seaman in search of seals, otters, and whales, hunting them almost to extinction. As the nomadic lifestyle of the Inuit was slowly destroyed, many turned to the whaling ships for wage work until, in 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia, and the whaling industry was finally restricted.

Gold, discovered in Nome in 1899, brought over 40,000 prospectors to Alaska, further changing the culture and ecology but also creating a market for Inuit ivory carvings. Skilled craftsman, the Inuit combined scrimshaw techniques learned from sailors, with their traditional images of hunting scenes or wildlife to create cribbage boards, seen here, butter knife sets, toothpicks, and baskets that catered to Victorian taste.

Inuit Peoples/h3>

Canada, Cape Dorset, Nunavut

Inupiaq Cribbage Board, ca 1900-1910

Walrus ivory tusk decorated with walrus and caribou, Etched and inked

2013.09.10

Gift of Dr. Jonathan Klarsfeld

-

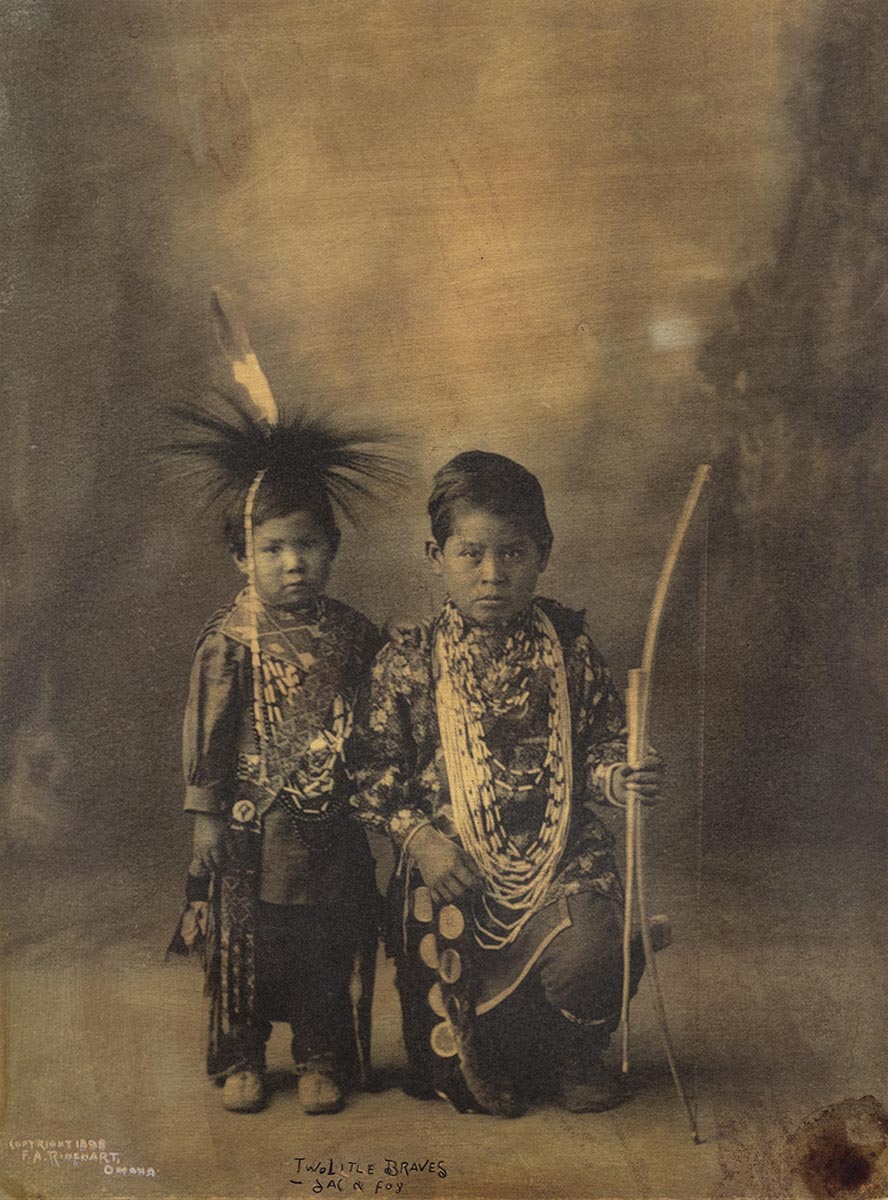

Frank A. Rinehart

American, 1861-1928

Two Little Braves, Sac and Fox, Omaha, 1898

(Tribal affiliation: Sauk and Fox Nations)

Platinum Print

2021.12.01

Gift of Dr. Donald Dworken

Beginning in the 1840s, showmen like P.T. Barnum and William “Wild Bill” Cody developed traveling shows that toured both America and Europe, providing popular forms of entertainment for the public. Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Circus* marketed artful deceptions, humbugs, and curiosities while Cody’s Wild West Show reinforced the myth of the American frontier as it reinscribed the tenets of Manifest Destiny.

By 1898, business and political leaders in Omaha, Nebraska developed the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, a world’s fair designed to showcase the agricultural success and economic development of the West. Included in the plan was an Indian Congress, hailed as a “serious ethnographic exhibition,” originally conceived by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, in partnership with the Smithsonian, to educate people about the culture and traditions of Native Americans simultaneously advancing the national policy of assimilation. Unfortunately, to the ire of the organizers, the exhibit ultimately buttressed familiar stereotypes when, with arrival of Cody, it was renamed Cowboys vs Indians Wild West Show. These so-called "living exhibitions," replete with mock Indian villages, war dances, and sham battles, whet the public’s appetite for sensation and spectacle while reinforcing “the commonly held understanding that Indians were an inherently violent and inferior people, and that their culture was incompatible with white progress.[1]

Commissioned by the Bureau of Ethnology, Frank A. Rinehart (ca. 1862-1928), with his assistant Adolph F. Muhr (ca. 1858-1913), documented over five hundred delegates from thirty-five tribes, however, it is important to note that these portraits, sold as postcards, also marketed and commodified ethnic identities. Nevertheless, Rinehart earned a reputation as one of America’s great chroniclers of indigenous cultures. As former photographic curator at the University of Kansas’ Spencer Art Museum, Tom Southall, observes:

The dramatic beauty of these portraits is especially impressive as a departure from earlier, less sensitive photographs of Native Americans. Instead of being detached, ethnographic records, the Rinehart photographs are portraits of individuals with an emphasis on strength of expression. [Although] not the first photographer to portray Indian subjects with such dignity, this large body of work which was widely seen and distributed, may have had an important influence in changing subsequent portrayals of Native Americans.[2]

[1] Omaha Daily Bee, September 1, 1898.

[2] https://dangerousminds.net/comments/beautiful_portraits_of_native_american

*To learn more about the history of Fairs, Carnivals and Circuses visit the exhibition on 3rd floor.

[1] Omaha Daily Bee, September 1, 1898. [1] https://dangerousminds.net/comments/beautiful_portraits_of_native_american*To learn more about the history of Fairs, Carnivals and Circuses visit the exhibition on 3rd floor.

-

INUIT ART

Inuit carvings from the prehistoric period are generally small and delicate; made of ivory, bone, antlers, or stone, and designed to be carried on a belt or worn as an amulet. The nomadic lifestyle of Native Alaskans limit ownership of larger objects, which are difficult to carry over long distances.

The historic period, beginning in the 1770s through 1949, reflects increased social interaction between indigenous peoples, whalers, missionaries, and traders from the south. These new groups exerted influence on the kinds of art that would be produced for trade and sale by the Inuit. Although traditional

subject matter continued to inform the content of works, the size and scale of works increased, indicating that work was made to satisfy market demands. Objects like toys, dolls, dice, and cribbage boards, seen here, were popular Items produced specifically to appeal to tourists.

Native Alaskan and Inuit artist collectives began to emerge during the contemporary period, post-1949. By the late 1950s and 60s, Native Alaskan and Inuit artist collectives secured recognition and financial support from the Canadian government to develop initiatives for marketing their art internationally. Traditional materials, such as ivory and bone, now seen as rare and expensive materials, were supplanted by soapstone, a cheap and plentiful material. Later, Hydrocal—a blend of gypsum and cement--was also used to make cast sculptures like Whale Rider. In addition, Inuit artists adopted such art-making processes as engraving, lithography, and silk-screening to satisfy the growing appetite of collectors.

Inuit Peoples/h3>

Canada, Cape Dorset, Nunavut

Left Image:

Seal Hunter

1977.01.04

Gift of Dr. Leonard Laskow

Right Image:

Carved Hydrocal

2013.09.01

Gift of Dr. Jonathan Klarsfeld

-

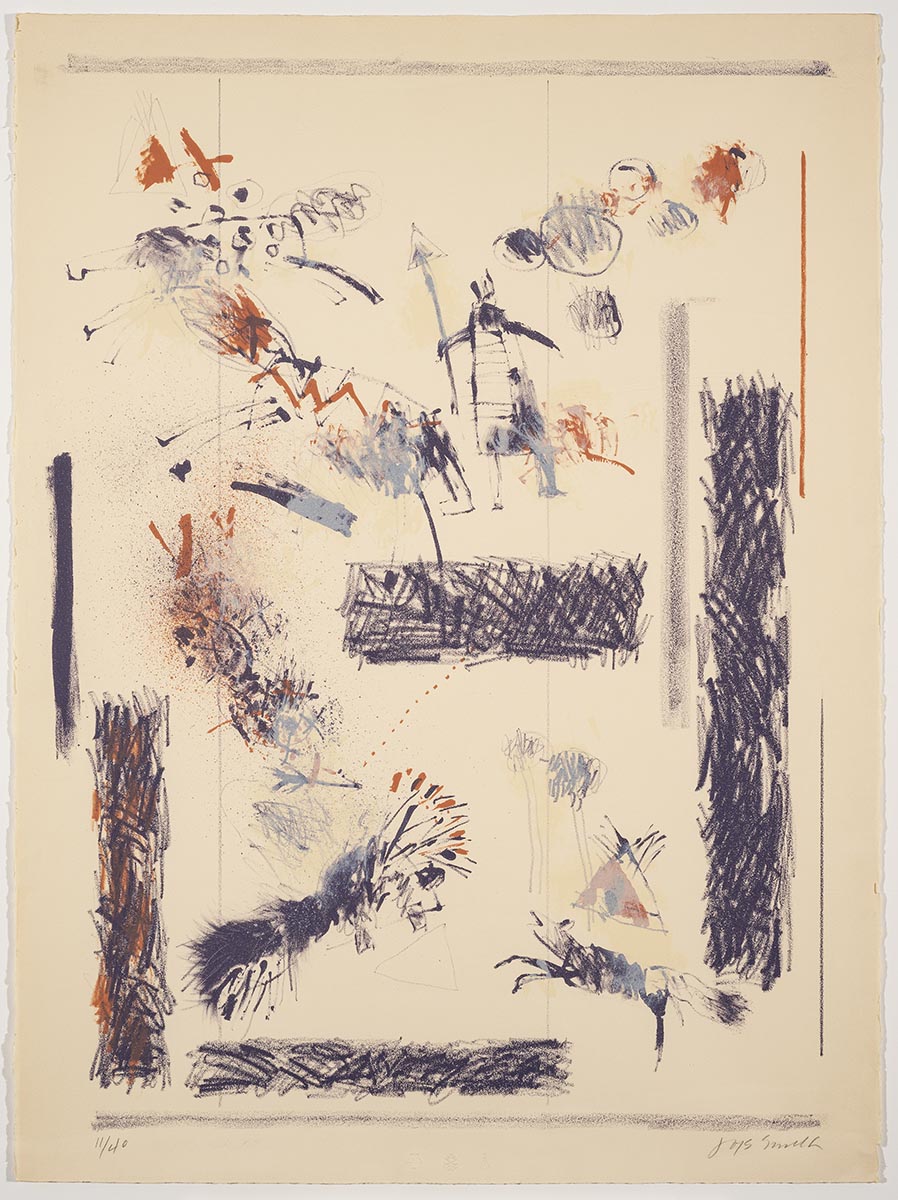

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Native American (Flathead Nation), b 1940

Untitled, 1979

Lithograph on buff Arches wove paper

1988.16.03

Gift of Burt and Anne Chernow

Internationally renowned painter, printmaker and artist, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith was born in Montana on the Flathead Reservation but grew up in California. Her middle name, "Quick-to-See," was given to her by her Shoshone grandmother as a sign of her ability to perceive and understand swiftly.

Smith’s imagery combines representational and abstract imagery blending her Native American culture with Western art practice to address tribal and U.S. politics, human rights, and environmental issues.

She received an Associate of Arts Degree at Olympic College in Bremerton Washington in 1960. She attended the University of Washington in Seattle, received her BA in Art Education at Framingham State College in Massachusetts in 1976 and a Master’s degree in art at the University of New Mexico in 1980.

Smith’s work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Quito, Ecuador; the Museum of Mankind, Vienna, Austria; The Walker, Minneapolis, MN; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC; the Museum of Modern Art and The Whitney Museum, both of NY.

-

Mukluks, 1900-1910

Sealskin, caribou fur, thread-sewn, White and brown fur cutouts and pompoms

2012.12.19

Gift of Dr. Jonathan Klarsfeld

Mukluks or kamiit boots are made from either reindeer skin, sealskin or caribou and form the outer layer of boots worn by the Inuit. These boots are worn over an inner boot liner to keep the feet warm. This design allows air to circulate and prevents foot sweat which could lead to frostbite, a major cause of morbidity.

-

Labrador Inuit Dolls (male and female), ca. 1920s

Carved wood with traditional costume

Wood, sealskin, deerskin, and cotton2013.08.13.01

2013.08.13.01Gift of S. Herman and Wendy Klarsfeld

The dolls seen here were most likely produced for the tourist trade. Both dolls are in excellent condition and show no sign of personal use as a child’s toy. Historically, Inuit girls would create dolls to develop their sewing techniques and to learn to make clothes. The traditional attire on these carved wooden figures is realistic, replete with hooded sealskin parkas (anorak), pants (qarliik), deerskin mittens (pualuuk) and boots (kamiit or mukluk).

Depleted Caribou herds and opposition to seal hunting by animal rights groups brought change to the indigenous lifestyle whereby hunting was no longer a primary occupation. And, with the adoption of manufactured European clothing, demand for skin garments diminished. Consequently, other skills, like making clothing, were no longer practiced, or taught. Although traditional garments are no longer used for daily wear, they may be worn on special occasions.

-

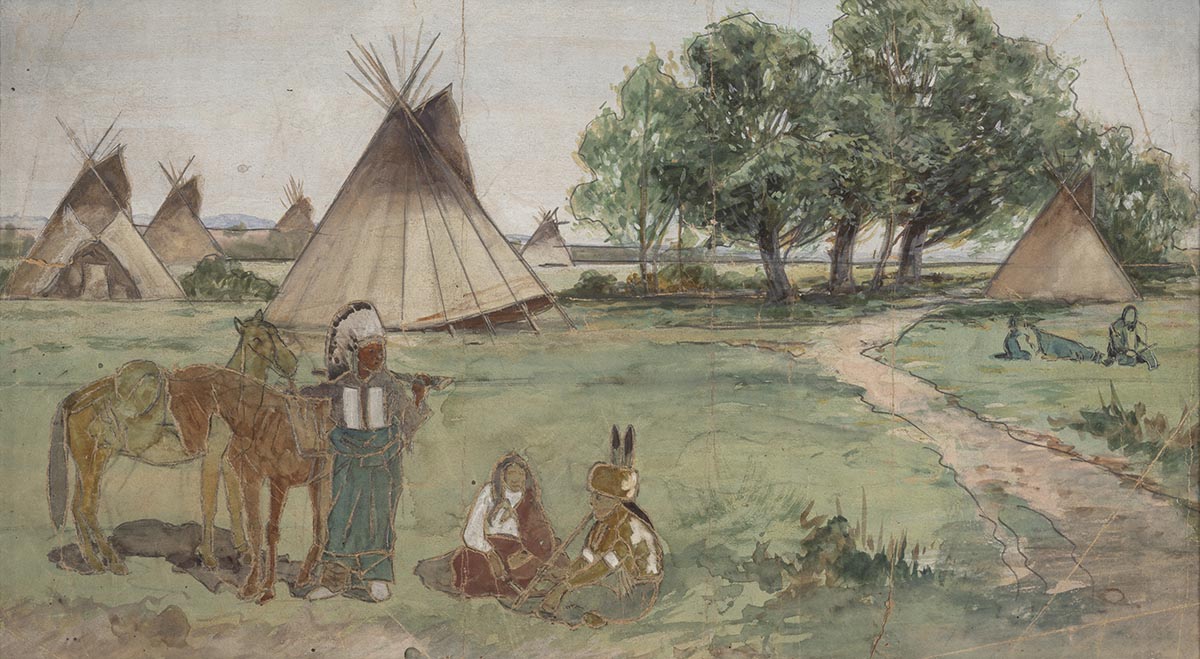

John Hauser

American, 1858-1913

Edge of the Encampment

Watercolor on paper

2018.23.01

Gift of S. Herman and Wendy Klarsfeld

Artist John Hauser was born in Cincinnati, Ohio to German immigrant parents in either 1858 or 1859. He began his formal training at the Art Academy of Cincinnati thereafter continuing his art studies with Thomas Noble at the McMicken School. Hauser enrolled at the Munich Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1881 and then travelled on to Paris. Upon his return in 1891, Hauser was offered a teaching position in the Cincinnati public schools but spent his summers in Arizona and New Mexico travelling with two other notable painters of Native Americans, Joseph Henry Sharp and Henry Farny. Hauser’s work offers viewers a glimpse into the traditions, clothing, and culture of the people he befriended and lived amongst. His sensitive portraits of Sitting Bull, Bald Face, Lone Bear and Red Cloud, among many others, radiate the deep admiration and empathy that he held for the people he chronicled all his life.

His respect and appreciation for the Sioux was reciprocated when both Hauser and his wife became honorary members of the Lakota Sioux in Pine Ridge, South Dakota in 1901. Today, Hauser’s work is valued not only for the historical portraits of important tribal chiefs, but also for capturing the vanishing lifestyle of Native Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

-

John Hauser

American, 1858-1913

Native American Scenes

Watercolor on paper

2018.26.02

Gift of Dr. Jonathan Klarsfeld

Artist John Hauser was born in Cincinnati, Ohio to German immigrant parents in either 1858 or 1859. He began his formal training at the Art Academy of Cincinnati thereafter continuing his art studies with Thomas Noble at the McMicken School. Hauser enrolled at the Munich Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1881 and then travelled on to Paris. Upon his return in 1891, Hauser was offered a teaching position in the Cincinnati public schools but spent his summers in Arizona and New Mexico travelling with two other notable painters of Native Americans, Joseph Henry Sharp and Henry Farny. Hauser’s work offers viewers a glimpse into the traditions, clothing, and culture of the people he befriended and lived amongst. His sensitive portraits of Sitting Bull, Bald Face, Lone Bear and Red Cloud, among many others, radiate the deep admiration and empathy that he held for the people he chronicled all his life.

His respect and appreciation for the Sioux was reciprocated when both Hauser and his wife became honorary members of the Lakota Sioux in Pine Ridge, South Dakota in 1901. Today, Hauser’s work is valued not only for the historical portraits of important tribal chiefs, but also for capturing the vanishing lifestyle of Native Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

-

Comanche, Southern Great Plains, North America

Child’s Shirt, 1900-1925

Buckskin, fringe, and beads

2018.26.08

The Comanche* people, which means enemy, were originally part of the Wyoming Shoshone tribe. Introduced to horses by the Spanish, they learned to ride, break, and trade horses and were renowned for their expertise, earning the title Lords of the Plains.

Skilled bison hunters, the Comanche followed the herds into new territory including parts of southeastern Kansas, Oklahoma, central Texas, southeastern Colorado, New Mexico, and northern Mexico, displacing through combat the tribes that had lived there. Bison sustained the Comanche, providing meat, tipis (tepees), thread (sinew), and robes. Deerhide, called buckskin, was used for clothing including moccasins, breechcloths, tunics, jackets, and shirts, like this one. Clothes, made by the women, were decorated with paint, porcupine quills, fringe, and beads.

The name Comanche was first used by the Spanish and then adopted by Euro-American soldiers and settlers. The Comanche called themselves Numinu or Nemene meaning true people.

-

Seneca People

Haudenosaunee Confederacy

Glengarry Cap with Niagara Floral Design, ca. 1830

Dyed moose hair, fabric, and beads in various colors

2020.20.05

Gift of S. Herman and Wendy Klarsfeld

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, referred to by the colonists as the Iroquois League, included the Onondaga, the Seneca, the Cayuga, the Oneida, the Mohawks and later, the Tuscarora. Their tribal lands included Montreal, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kentucky, and parts of the Ohio Valley. The Confederacy had a long history of trading with the Dutch, French, and British as well as the settlers especially for beaver fur, which was in high demand in Europe. Over the ensuing years, through a combination of warfare, broken treaties, eminent domain, and continuous encroachment by new colonizers, the member tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy were forced to either assimilate or move ever westward.

Beadwork was a rich tradition practiced by the Haudenosaunee for centuries. Materials included bones, shells, and polished stones until the 15th century when, through trade, glass beads, needles and velvet became available. By the nineteenth century, Niagara Falls, which straddles Canada and New York, became a popular travel destination for both Europeans and Americans, providing the Haudenosaunee with a tourist market eager for handmade items unique to the location. The raised beadwork styles, especially those created by the Seneca and Tuscarora, used to decorate the Glengarry bonnets and beaded bags, like those on view here, were highly valued by fashion-forward ladies of the Victorian era. According to art historian Ruth Phillips, this cap style was derived from the traditional Scottish Highland dress…reminiscent of the military uniforms worn by British soldiers in Canada and popularized, both here and in Britain, when Queen Victoria began dressing her sons in these styles. * Raised Haudenosaunee beadwork, created for the market, is recognized as one of the most distinctive types of embroidered beadwork ever made and continues to be prized by contemporary collectors.

* Ruth Phillips, Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900 (Seattle: University of Washington Press / Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998).

-

Tonawanda Seneca

Haudenosaunee Confederacy

Chatelaine Bag, 1840-1860

Fabric, glass beads in various colors, and clasp

2020.21.04

Gift of Dr. Jonathan Klarsfeld

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, referred to by the colonists as the Iroquois League, included the Onondaga, the Seneca, the Cayuga, the Oneida, the Mohawks and later, the Tuscarora. Their tribal lands included Montreal, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kentucky, and parts of the Ohio Valley. The Confederacy had a long history of trading with the Dutch, French, and British as well as the settlers especially for beaver fur, which was in high demand in Europe. Over the ensuing years, through a combination of warfare, broken treaties, eminent domain, and continuous encroachment by new colonizers, the member tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy were forced to either assimilate or move ever westward.

Beadwork was a rich tradition practiced by the Haudenosaunee for centuries. Materials included bones, shells, and polished stones until the 15th century when, through trade, glass beads, needles and velvet became available. By the nineteenth century, Niagara Falls, which straddles Canada and New York, became a popular travel destination for both Europeans and Americans, providing the Haudenosaunee with a tourist market eager for handmade items unique to the location. The raised beadwork styles, especially those created by the Seneca and Tuscarora, used to decorate the Glengarry bonnets and beaded bags, like those on view here, were highly valued by fashion-forward ladies of the Victorian era. According to art historian Ruth Phillips, this cap style was derived from the traditional Scottish Highland dress…reminiscent of the military uniforms worn by British soldiers in Canada and popularized, both here and in Britain, when Queen Victoria began dressing her sons in these styles. * Raised Haudenosaunee beadwork, created for the market, is recognized as one of the most distinctive types of embroidered beadwork ever made and continues to be prized by contemporary collectors.

* Ruth Phillips, Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900 (Seattle: University of Washington Press / Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998).

-

Telling Stories

The Cochiti Pueblo’s rich tradition of making figurative pottery, called Storytellers, can be traced back to 400 CE. In the 16th century, the Spanish invaded this territory and outlawed the practice of making these sculptures, which were considered “false idols,” and they sought to convert the indigenous population to Christianity. The arrival of the railroad in the late 1800s opened up vast areas of the West, bringing with it White tourists which, in turn, stimulated the resurgence of these small, easily portable souvenirs. And, by the early 1900s, the production of these clay figurines by the Cochiti spread to other Southwest pueblos reinvigorating both an art and an industry. The most popular sculpture, known as Singing Grandmother, seen here, depicts a woman telling a new generation the stories of their shared history and culture.

Judy Toya

Water Clan, Jemez Pueblo, 1953

Storyteller: Grandmother with Three Children, 1990

Black and red pigment on tan clay

2021.13.01

Gift of Robbin Zella

-

Tlingit Peoples

British Columbia and Alaska

Mosquito Headdress, ca 1890

Carved wood with whitewashed head with pigment in black, yellow, and red; articulated wings attached to side of head with wood pegs

2021.23.17

Gift of S. Herman and Wendy Klarsfeld

The beliefs and myths of Tlingit people are drawn from living creatures observed in nature and are part of their storytelling tradition. The Mosquito Headdress, on view here, would have been worn by the leaders of the Tlingit people during dance rituals, funerary rites, and festive events or to reenact the creation myth of this blood-sucking insect.

According to Tlingit folklore, there lived a giant cannibal on the mountain nearest their village, and periodically he would invade, eating as many people as he could capture. Terrified all the time, especially for the safety of their children, the villagers held a meeting and devised a plan to rid themselves of this menace. They decided to trap and kill the giant cannibal. A deep pit was dug and filled with wood. To disguise the pit, a net made of sinew was stretched across the opening and covered with leaves and branches to blend with the forest floor. The most agile and quickest hunter drew the giant cannibal into the woods, luring him towards the trap. Hungry and ready to eat, the giant cannibal soon gave chase and plunged into the deep hole from which he could not escape. The villagers, carrying torches, gathered round the pit and tossed the fire onto the dried wood. They kept the fire burning for four days and four nights. The villagers stirred the ashes to assure themselves that the giant cannibal was completely gone, but as the fire died down, they heard his voice: You can never kill me, I will always feed on you! Ashes and sparks began to fly up from the pit transforming into mosquitoes that immediately began to attack the villagers. And so, it seems, the Giant kept his vow.

-

Telling Stories

The Cochiti Pueblo’s rich tradition of making figurative pottery, called Storytellers, can be traced back to 400 CE. In the 16th century, the Spanish invaded this territory and outlawed the practice of making these sculptures, which were considered “false idols,” and they sought to convert the indigenous population to Christianity. The arrival of the railroad in the late 1800s opened up vast areas of the West, bringing with it White tourists which, in turn, stimulated the resurgence of these small, easily portable souvenirs. And, by the early 1900s, the production of these clay figurines by the Cochiti spread to other Southwest pueblos reinvigorating both an art and an industry. The most popular sculpture, known as Singing Grandmother, seen here, depicts a woman telling a new generation the stories of their shared history and culture.

Barbara Scavotto-Earley

American, 1951

Storyteller: Evening Song, 1989

Ceramic with gray and white glaze

2022.07.01

Gift of Robbin Zella

-

Navajo “Eyedazzler” Germantown Weaving, 1880-1910

Aniline dyes, yarn, and wool warp

2018.26.02

Gift of Dr. Jonathan Klarsfeld

Traditionally, Navajo blankets were originally produced using handspun Churro wool colored with natural dyes. By 1868, machine woven yarn produced in Germantown, Pennsylvania soon became available to the Navajo through the trading posts that sprung up along the railway stations. These weavings, known as Eyedazzlers, refer to the bright colors and zig-zag designs with serrated edges, seen here. Produced specifically for trade and for sale, affordable small squares or rectangles were sold to tourists. The larger, and more expensive, blankets, rugs, and serapes, created by master weavers, were reserved for collectors such as the renowned publishing magnate, William Randolph Hearst.