Alberta Cifolelli Essay

Cifolleli Home Page | Essay by Mark Daniel Cohen | About the Artist

The Brightening of the Spirit in the Art of Alberta Cifolelli

Mark Daniel Cohen

All art is emblematic of a state of affairs within. All art is tinctured and leaned into a posture of the soul, composed and made radiant with a hue of inclination, a coloration of a passion. It is the heightened, vivifying intent and instigation that notes the nature and function of art, and to speak of an unimpassioned art is to commit a contradiction in terms. Such work is just poor journalism and meager editorializing.

The vitality of art is an increment of awareness, and it sets the difference between mere knowledge and full-bodied understanding, between a recognition of the facts and a profound appreciation of the truth — a deeply felt and intuited apprehension of the vibrant atmosphere that surrounds every moment, every place, every vision. This is what art is for — for the appreciation of mood, of mood as a perceptive means, as an insight into the most profound significance of the world and of ourselves within it. And there is something of the eternal to it, for in the realm of human awareness, our compendium of moods is what we have always had in common, shared across the world and across the ages. The moods ever have remained the same.

And ever have they been the soul of art, for the purpose of art has always been to encapsulate and convey the moods of experience felt as a living quantity, of experience as it is fully known, with all our senses engaged. It is a purpose that cannot change, and we see it today, as much as ever, in the works of every strong, mature, and bracingly vivid artist, in the works of artists such as Alberta Cifolelli.

As is evident in the paintings, pastels, and charcoal drawings in the current exhibition, Cifolelli’s art is emblematic of a moment. It is a moment not as we measure on the clock and calendar of our hours and days — rather, a moment in the arc and journey of the spirit, a mark gauged on the developmental line of the inner life, a state of being so fully realized it stands apart and feels as if it leads no further, so thoroughly is it itself. It is the kind of moment that, when it arises in the course of living, we remember forever. For Cifolelli, it is a moment of infusion, of an incursion, of the ingress of an intangible sensation that breaks upon us like a dawn. Hers is the moment of the brightening of the spirit — a time in which the mind and the feelings quicken, lift in a distilled authenticity of joy, and acquire the élan of pure life.

As is evident in the paintings, pastels, and charcoal drawings in the current exhibition, Cifolelli’s art is emblematic of a moment. It is a moment not as we measure on the clock and calendar of our hours and days — rather, a moment in the arc and journey of the spirit, a mark gauged on the developmental line of the inner life, a state of being so fully realized it stands apart and feels as if it leads no further, so thoroughly is it itself. It is the kind of moment that, when it arises in the course of living, we remember forever. For Cifolelli, it is a moment of infusion, of an incursion, of the ingress of an intangible sensation that breaks upon us like a dawn. Hers is the moment of the brightening of the spirit — a time in which the mind and the feelings quicken, lift in a distilled authenticity of joy, and acquire the élan of pure life.

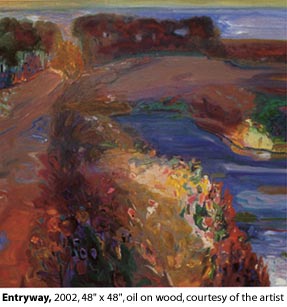

One can see the temper of her vision in Cifolelli’s subjects. It is in her universal images of nature — in the freshness and cleansing purity of idyllic, bucolic scenes and her intricately devised, personally imagined floral studies, each as individual and revealing as a signature. The incursion of inward brightness can be felt in the landscapes, which almost always contain a pathway — inescapably evocative of a transition, of a transformation within the imagination, of a journey taken to an elsewhere we can only discover. The path is there in almost every instance: in the works whose titles confess the movement along a new way — such as Ways in Cortona, Entryway, Fertile Ways, and Gateway — as well as in many that claim by title another issue — Motherland III, IV, and V, Passion Fruit, and Exterior I. And the sheer import of the vision, the momentousness of the moment, is heralded by bouquets that stand before landscapes like sentinels, guarding and granting entrance to the path of the insight, as in Uno Via, and The Sentinels II, III, VIII, and IX.

Yet, the vision of the brightening fall is not in nature, but in nature imagined, transformed, reconceived into art. And it is not in Cifolelli’s subjects so much as it is in her technique, not in what is rendered but in the way it is rendered. Cifolelli paints much as she sketches. For all the strength and pertinence of her colors, for all their powers of evocation, the living brilliance of their suffusion, it is mark-making that is her thought. As she has told me, every mark is considered and decided, every mark is a moment of significance. Together, they composite a calligraphy of inner movement. You feel their action as much as see it. The bristling strokes, each of a particular configuration, assemble like suspicions. They flock and activate the spirit like inklings, like suggestions of things beyond comprehension running along the skin, like implications of the flesh, making you feel your entire body as an organ of perceiving sense, as a means of feeling the art. The marks pass you through the works as much as visualize them, entering you into them, like gate-keepers, or sentinels.

There is a quality of abstraction in this, for the purpose of abstraction has always been to achieve and insure precisely what is evidently Cifolelli’s purpose — to amplify and maximize the artistic effect, to eliminate aesthetically extraneous and ineffectual material from the work and leave it pure art. And there should be nothing surprising in this. Despite her consistent reliance on natural subject matter, on recognizable imagery, Cifolelli’s manner is essentially that of abstraction. Studied for its historical precedents, abstraction is nothing more than an emphasis on style, an increase in the temperature of the technique, a heightening of the ratio of method to image. And in Cifolelli’s art, when properly seen, it is the marks you see first. The principal image is not nature, but her calligraphy of mood.

That calligraphy is coordinated into a complete effect, into a transport of imagined sensation, and often the orchestration is such that it reaches a crescendo. Ways in Cortona is a landscape composition, but more particularly it is a pure integration of marks and color fields. The isolated, configured and deliberate brush strokes braid and intricate the inner vision, allowing the imagination no rest, swaying it in a continuous and gentle turbulence. The fields of color are densities of tone, heavy with a luxuriance of color, executed in glazes such that you see through diffractions of hue and rainbow spectra. The colors are so dense they are like jewels, like inlays of precious stone. You enter their washing thickness, and they are so heavy with hue you can almost taste them, so thick you feel their depths, and there are moments of the milky translucence of chalcedony, of white breaking up like a wave to bathe you in the sensation. You feel your body passing through the deepening layers of hue, drifting in, swimming in the color, buoyed by it. Despite the evident subject, as an act of imagination this is an underwater dream, and that makes it an entry into the unconscious, a diving down to the depths of the mind, an incursion into another world our daylight lives do not know.

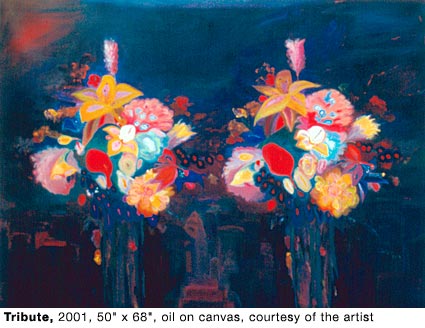

The most extraordinary and compelling mood in the exhibition may be in Tribute — Cifolelli’s one dark vision and a work done in memory of the September 11 tragedy at the World Trade Center. As an image, it is simple: two floral bouquets stood before a vaguely rendered cityscape. But as an artistic imagining of orchestrated mood, it is stunning. The detonation of color — like gems set in darkness, shimmering in a near void — is like a cracking of the heart. The purity of mood here is a purity of pathos. This the feeling of tragedy: it is the beauty of heartbreak, and the heartbreak of beauty, for true beauty is never without a central sadness. It is a crucial accomplishment, for oddly, there is little tragic art in our time, and ours is a time of tragedy. Not just of calamity, but of tragedy — of wreckage that comes and feels inescapable, as if it were the will of the gods. It is strange that contemporary artists have been slow to pick this up. It is the challenge of the moment. But then, perhaps it is not so strange, for tragedy is not for the young. It requires artists of maturity and inner strength, artists of achievement, artists capable of doing what is difficult — artists like Alberta Cifolelli.

Tragedy is difficult not merely because it is tragic, but because it is mythic — an entry into a moment that is an encapsulation and a living embodiment of an essential condition of our existence. This is always Cifolelli’s pursuit: the ingress into the moment of greatest significance, into the moment that holds some portion of the unalterable meaning of our lives, holds it like an atmosphere — a moment that is timeless and that contains somehow the rest of time and existence in it. The revelation of such states is at the heart of the artist’s enterprise, just as it is at the heart of the sacred. In her apparent floral studies and natural landscapes, Cifolelli tells us as much, with titles such as Inalienable for All Time and Sacred Entry I and II. And she shows it as clearly as any artist can in Temple III, a seemingly simple painting of a tree on an island in a lake. The composition, reminiscent of Piero della Francesca’s Ideal City and Raphael’s Sposalizio della Vergine, is one in which space becomes circular, surrounding the temple/tree at the center of the work and seeming to radiate out from it like an invisible and dazzling light, light propagated by the density of the color that holds it. This is space itself — pure geometry — as a vehicle of insight, as something holy, and through it, Alberta Cifolelli conveys a vision of life as sacred, as inalienable for all time, life that is in its entirety a single, timeless moment, a moment of unalloyed brilliancies.

Tragedy is difficult not merely because it is tragic, but because it is mythic — an entry into a moment that is an encapsulation and a living embodiment of an essential condition of our existence. This is always Cifolelli’s pursuit: the ingress into the moment of greatest significance, into the moment that holds some portion of the unalterable meaning of our lives, holds it like an atmosphere — a moment that is timeless and that contains somehow the rest of time and existence in it. The revelation of such states is at the heart of the artist’s enterprise, just as it is at the heart of the sacred. In her apparent floral studies and natural landscapes, Cifolelli tells us as much, with titles such as Inalienable for All Time and Sacred Entry I and II. And she shows it as clearly as any artist can in Temple III, a seemingly simple painting of a tree on an island in a lake. The composition, reminiscent of Piero della Francesca’s Ideal City and Raphael’s Sposalizio della Vergine, is one in which space becomes circular, surrounding the temple/tree at the center of the work and seeming to radiate out from it like an invisible and dazzling light, light propagated by the density of the color that holds it. This is space itself — pure geometry — as a vehicle of insight, as something holy, and through it, Alberta Cifolelli conveys a vision of life as sacred, as inalienable for all time, life that is in its entirety a single, timeless moment, a moment of unalloyed brilliancies.

All art by Alberta Cifolelli is ©Alberta Cifolelli/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. No part of this publication may be duplicated without the written permission of the Artist and The Housatonic Museum of Art except for brief quotations and reproduction for the purpose of reviews and promotional materials.